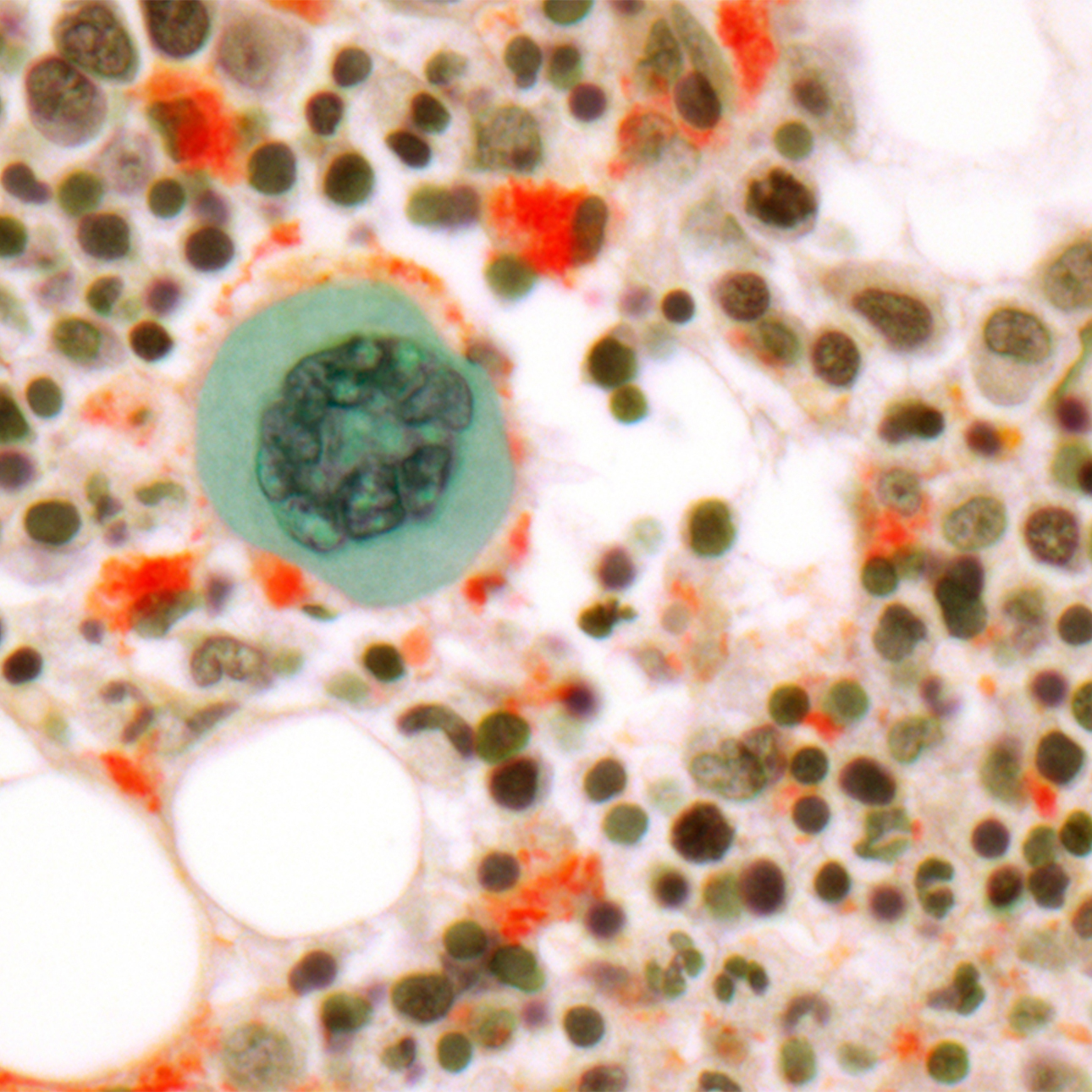

Acute Myeloid Leukemia

Treatments

Patients with AML undergo extensive evaluation including:

- Medical history and physical examination

- Blood tests

- Heart tests

- Bone marrow aspiration with biopsy

- Immunophenotyping of the marrow to define protein expression in leukemia cells

Doctors review this information to confirm the AML subtype. Treatment begins as soon as possible and varies by age, general condition and cytogenetics results. For most patients age 69 or younger, the goal is a cure. Typical therapy includes three phases:

- First phase — Induction chemotherapy

- Second phase — Consolidation chemotherapy, which may include stem cell transplantation

- Third phase — In some cases, blood or marrow transplant (BMT)

One AML subtype, called acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), has a unique biology and is treated differently. This type of leukemia is treated with a vitamin pill called all trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) and arsenic together with chemotherapy. Most people undergo multiple cycles of this therapy. Bone marrow transplantation is rarely needed.

First phase: Induction chemotherapy

The goals of induction chemotherapy are to eliminate leukemia cells from the blood and bone marrow and to induce a remission. A complete remission is defined as having no visible leukemia cells in the blood or bone marrow and having normal blood counts without the need of transfusions.

Induction therapy for patients under the age of 70 typically includes ARA-C, daunorubicin and occasionally etoposide chemotherapy. The medications are given over a six- to seven-day period. Although side effects are expected and can be severe, our team is very skilled at caring for patients undergoing induction therapy for AML, administering all needed supportive care measures, such as transfusions, antibiotics and medications.

During most of the hospital stay, patients receive intensive supportive care to protect them during their period of very low blood counts, including transfusions of red blood cells and platelets to correct anemia and to prevent bleeding. Antibiotics are used both preventatively and to treat bacteria and fungal infections. Additional antibiotics may be needed if other infections occur. Growth factors such as G-CSF (Neupogen) can help bring the patient's white blood count back more quickly and may help prevent infections.

The chemotherapy agents also are associated with complete but temporary hair loss, sores in the mouth, and throat and skin rashes. Other support care measures include anti-nausea drugs to prevent or decrease nausea, anti-diarrheals to decrease diarrhea, eye drops to prevent irritation and nutrient-rich beverages to improve nutrition.

Patients are expected to be hospitalized for four to five weeks. Once the blood counts have returned to normal and the bowels function normally, patients may be discharged from the hospital. At the end of the induction therapy, a bone marrow biopsy is performed to see if a complete remission has been achieved. Approximately 70 percent to 80 percent of patients are expected to enter complete remission.

If a complete remission is achieved, patients are then given a one-month break to prepare for the second (consolidation) treatment cycle.

Second phase: Consolidation chemotherapy

Once a patient achieves a complete remission more chemotherapy is needed to destroy any residual leukemia in the body. Consolidation chemotherapy can consist of the following:

- Additional cycles of intensive chemotherapy.

- A bone marrow transplant using one's own blood or marrow, called an autologous transplant.

- A bone marrow transplant using blood or marrow from a donor, such as a brother or sister or unrelated person. This is called an allogeneic transplant.

The type of consolidation therapy offered to any particular patient depends on the subtype of leukemia, the initial chromosome analysis and the expertise of the leukemia doctor and center.

This second phase of treatment will likely include similar chemotherapy medications including the drug ARA-C (cytarabine), sometimes with etoposide. The actual number of chemotherapy cycles required during consolidation as well as the need for a stem cell transplant varies from case to case.

In general, consolidation treatment has similar toxicities as induction therapy and also requires intensive supportive care. At some institutions, the consolidation treatments can be done as an outpatient, but most patients are treated in the hospital and require a four- to five-week hospitalization. Overall, approximately 30 percent to 40 percent of patients receiving consolidation chemotherapy are cured of their AML.

If a patient is going to have an autologous bone marrow transplant, his or her stem cells are collected after the consolidation chemotherapy stage is complete and once his or her blood counts recover. A process called "mobilization" enables the collection of stem cells from the blood. When the white blood cell counts are more than 10,000 cells/uL, a large IV catheter called a Quentin catheter is inserted into one of the large veins in the neck. This catheter is connected to an "apheresis" machine that separates the blood into individual components allowing the collection of only the white blood cells. All the other cells, including red blood cells and platelets, are given back to the patient. Each apheresis procedure takes four hours, and two to three procedures are usually necessary to collect enough stem cells.

Once the stem cells are collected, and all other toxicities have resolved, the patients may be discharged from the hospital. The stem cells are frozen and saved for future use. Patients are then given a one-month break to prepare for high-dose chemotherapy and the re-infusion of the stem cells.

High-dose chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation

BMT is also called stem cell transplantation, and is often recommended for AML patients with intermediate and poor risk features. UCSF Medical Center has an expertise in autologous stem cell transplantation for AML. Autologous stem cell transplantation — using cells collected from the patient's own bone marrow after they have achieved complete remission — appears to produce a cure approximately 50 percent to 55 percent of the time for intermediate-risk AML.

This stage of treatment is both the most important and most dangerous. This therapy requires a one-month hospitalization. The goal of this therapy is to utilize much higher doses of chemotherapy to completely destroy any residual leukemia cells. The side effects are rather severe and the chance of dying from complications associated with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplant is 1 to 2 percent.

The chemotherapy medications include Busulfan and etoposide, which are administered over five days. After two days of chemotherapy, the frozen stem cells will be re-infused into an IV catheter. The rest of the hospitalization consists of waiting for the new stem cells to grow, and during this time supportive care is administered as needed. Once the blood counts have improved and the other side effects have resolved, patients may be discharged. Patients are followed closely in the outpatient clinic for approximately three months. Most patients are able to return to work within three to six months of transplantation.

The preferred treatment for patients with good or intermediate-risk chromosome test results is autologous stem cell transplantation, while allogeneic transplantation is favored for those with high-risk chromosome test results.

Allogeneic transplantation using stem cells or bone marrow from a tissue-matched brother or sister or unrelated donor produces cure rates of approximately 50 percent to 60 percent in patients with intermediate-risk AML. However, allogeneic transplantation is significantly more difficult and dangerous than either chemotherapy or autologous transplantation, and 15 percent to 30 percent of patients do not survive the first year of treatment. For this reason, it is often reserved for more difficult cases.

Poor-risk AML patients are best treated with allogeneic transplant despite its difficulties and dangers. Cure rates of 20 percent to 25 percent may be achieved. For patients with poor-risk leukemia who do not have a matched sibling donor, an unrelated donor may be sought through the National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP).

Investigational therapies

UCSF is dedicated to improving outcomes for AML patients through the use of investigational therapies and clinical research trials.

Recent efforts focus on increasing the busulfan dose during autologous transplant, treating older patients with chemotherapy packaged in balls of fat (liposomes) to decrease side effects and possibly increase remission rates, and treating patients with AML derived from myelodysplastic syndromes or from therapy for other cancers with experimental chemotherapy agents thay may be more likely to achieve remission.

New research is in progress to treat AML patients with a gene mutation in their AML cells, called FLT3, with new non-chemotherapy drugs that "target" the abnormal protein made from the mutated FLT3 gene.

UCSF Health medical specialists have reviewed this information. It is for educational purposes only and is not intended to replace the advice of your doctor or other health care provider. We encourage you to discuss any questions or concerns you may have with your provider.

Treatments we specialize in

-

Allogeneic Transplant

In a procedure similar to a simple blood transfusion, the patient receives bone marrow or stem cells from a tissue-matched donor.

Learn more -

Autologous Transplant

Stem cells collected from the blood before chemotherapy or radiation are returned to the patient's body using a process similar to a blood transfusion.

Learn more