Erectile Dysfunction

Overview

Erectile Dysfunction, or ED, is difficulty or inability to attain and maintain an erection sufficient for satisfactory sexual activity. ED is a relatively common problem, affecting up to 30 million men of all ages in the United States and more than 150 million worldwide. The ability to have an erection requires complex coordination among nerves, blood vessels, muscles and the brain.

A variety of factors – frequently in combination – can cause ED. These factors include neurological, hormonal and vascular disorders, as well as the natural aging process and certain chronic diseases. ED is also a common side effect of treatments for prostate cancer. In addition, psychological issues, such as depression, anxiety or performance concerns, play at least some part in virtually every case of ED.

What is ED?

Male sexual function has traditionally been thought of as a linear process: A man feels sexual desire, blood flows into the penis, and it goes from flaccid to very firm – an erection. After a period of sexual excitement or activity, the man experiences ejaculation (release of semen), which is typically accompanied by orgasm (intense pleasure and release of neuromuscular tension). It is important to understand that ejaculation and orgasm are separate processes that may occur independently. Also, men can experience ejaculation or orgasm without having an erection.

The usual process of male sexual function can be derailed by various circumstances, including:

- Decreased sexual desire, also referred to as decreased libido, is common and may occur when a man is depressed, anxious, stressed or having problems with his sexual partner. Some health conditions are associated with decreased desire, as are low blood levels of testosterone, the male hormone.

- Problems with ejaculation (such as decreased volume and changes in consistency) can result from certain treatments for prostate problems, including medications, surgeries and radiation therapy. Ejaculation changes are also common as men age.

- Though our current scientific understanding of the experience of orgasm is limited, we know that many factors – emotional, psychological, physical – contribute, and changes in these can diminish the experience. Changes in ejaculation also influence the perception of orgasm for some men, while others experience ejaculation but have a mild or even no sensation of orgasm.

Men coping with ED do best when they let go of the idea that sexual function depends on the ability to have a rigid erection and an ejaculation. A careful assessment of sex life and the health of the sexual relationship are important to producing the best outcomes when addressing any type of sexual problem. Remember that mutually satisfying sexual relationships can be maintained in the presence of ED or other sexual challenges. For more information about this, refer to the books listed at the end of these pages.

Who gets ED

The single biggest factor associated with ED is aging. Men are at higher risk as they get older (see chart below). Having any of the following can elevate ED risk:

- Chronic medical conditions, such as cancer, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, heart disease or diabetes

- Vascular disease

- Neurological injuries, such as from having a stroke

- Hormone deficiency, including receiving androgyn deprivation therapy for prostate cancer

- Smoking habit

- Obesity

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Major pelvic surgery or radiation therapy, especially for prostate or bladder cancer

*Chronic disease includes other cancers, high blood pressure, heart disease, diabetes and a history of stroke.

†Risk factors include chronic vascular conditions (such as high blood pressure, diabetes or high cholesterol), tobacco use, obesity, lack of exercise, neurological injuries and hormone deficiencies.

Data from Ann Intern Med. 2003 Aug 5; 139(3): 161-8. Printed with permission from the American College of Physicians.

Our approach to erectile dysfunction

UCSF is a national leader in treating urological disorders, including male sexual dysfunction, urinary incontinence, pelvic pain, urinary stone disease, male infertility and prostate disease. We offer the full array of therapies, including the latest techniques, and our team is committed to providing innovative, highly skilled care with compassion.

Treatment

A number of treatments can help patients attain and maintain a rigid penis for sexual activity. Which is right for you depends on the cause of your ED, your age, your general health, and your and your doctor's preferences. Most often, providers recommend a stepwise approach that starts with the simplest or least intrusive option. While this approach is appropriate for most patients, you may choose to skip or avoid some of the available treatment options. The overarching goal – to re-establish sexual intimacy and pleasure – can be achieved in a number of ways. As you make treatment decisions, make sure your doctor understands your priorities.

Coping with ED

Treatments for ED are generally effective but don't work in every case. Patients may avoid certain treatments altogether for a variety of reasons. If you can't find an effective or acceptable solution, you still have options for enabling sexual intimacy and pleasure. Patients who can't achieve a rigid erection may still enjoy cuddling, genital caressing or oral sex. With a supportive partner, patience and willingness to explore different ways of being sexual, most patients are able to achieve satisfaction, including orgasm, regardless of whether they can get sufficiently erect for penetrative sex.

A good way to resume your sex life combines being open to options with adopting a gradual approach that ensures you and your partner feel comfortable at every step. Sensual, mutually pleasuring activities with no performance goal can allow you to be intimate without stress.

Sometimes partners need to redefine their sexual relationship after cancer treatment. In the past, they may have considered kissing, caressing and oral sex as simply intercourse foreplay, yet arousing one another and even reaching orgasm without intercourse can allow physical pleasure and emotional closeness to be shared without the need for a rigid erection. Your sex life should be based on what you and your partner mutually define as sexually pleasurable and satisfying, and this doesn't have to include penile hardness or penetration. Many patients use vibrators to achieve orgasm.

Patients often overestimate their partner's feelings on the importance of penetration, so rather than making assumptions, patients should talk to their partners about what matters to them. If penetration is an important part of a couple's sex life, they have a number of medical options that will help with achieving a rigid erection for penetration.

If you'd like sexual or marriage advice or counseling, please ask your provider for a referral. The American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors and Therapists and Society of Sex Therapy and Research provide valuable information and searchable list of credentialed experts on sexual wellness.

| Type of therapy | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Oral medication (Viagra, Levitra, Cialis, Stendra) |

|

|

| Medicated urethral suppository for erections (Muse) |

|

|

| Penile injections |

|

|

| Vacuum device |

|

|

| Penile prosthesis |

|

|

Oral medications

In the United States, four oral medications are available for treating ED: Viagra (sildenafil), Cialis (tadalafil), Levitra (vardenafil) and Stendra (avanafil). These drugs facilitate erections by improving blood flow to the penis. These medications must be followed by sexual stimulation – otherwise, they will have little effect. They also may not work if the cavernous nerves (which are involved in erections) are injured, as can happen with surgery or radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Overall, the likelihood of responding to these drugs is around 70% to 80%, depending on age, general health and other factors. Compared with patients taking a placebo, those taking any of these drugs report higher satisfaction with overall sexual function, orgasm, penile rigidity and erection maintenance.

We also use oral medications as a form of penile rehabilitation for patients who have undergone radical prostatectomy, radiation therapy or hormone therapy. The underlying theory is that enhanced blood flow may spur recovery of spontaneous erections by keeping the penile tissues well supplied with blood. Although there's no evidence that use of these drugs will help patients recover the ability to have spontaneous erections after prostate cancer surgery, there's little harm in their judicious use for ED. The short-term enhancement of erectile response provided by the drugs may help facilitate sexual encounters and maintain intimacy while patients recover from prostate cancer treatment.

Viagra and Levitra remain in the bloodstream and can help patients achieve erections for about six to eight hours. Cialis is a long-acting medication that may have an effect for 36 hours. Stendra stays in the circulation for a period somewhere between those of Viagra or Levitra and Cialis. Studies show that all four drugs are generally well tolerated. There's no convincing evidence that any one is better than the others, although individuals may have personal preferences.

Patients at risk for heart attack or stroke should consult their providers before engaging in sexual activity, as exertion during sex can strain the heart. Patients who take nitrate medications shouldn't take any of these drugs, as the combination can cause a potentially life-threatening drop in blood pressure. Caution should also be exercised in patients who take alpha-blockers, which are commonly used for prostate problems and for high blood pressure; there is a small potential for a drop in blood pressure if both medications are taken at the same time. Doses of an ED drug and an alpha-blocker should ideally be separated by at least four hours.

The following chart shows how we prescribe these medications at UCSF. Please consult doctor about the right dosage for you.

| How to take oral medications (Viagra/Levitra/Cialis/Stendra) | |

| Viagra (sildenafil) |

|

| Levitra (vardenafil) |

|

| Cialis (tadalafil) |

|

| Stendra (avanafil) |

|

| For all of these medications, if you don't achieve an erection after six attempts that include stimulation, speak with your provider about adjusting the dose or trying a different treatment. | |

| Side effects for all oral medications listed above |

|

| Things to remember for all oral medications listed above |

|

Penile rehabilitation

Penile rehabilitation is a strategy for helping patients regain erectile function following surgery or radiation for prostate or bladder cancer. The theory behind the treatment is that poor blood flow after cancer treatment leads to scarring and shrinkage of the penis. In this context, even if the nerves recover over time, changes to the penis itself may make erections difficult. Theoretically, if blood flow to the penis can be maintained, the tissue may be less prone to scarring and shrinkage. This is typically accomplished by administering regular doses of Viagra, Levitra, Stendra or Cialis without the patient necessarily planning to have sex. In some cases, physical exercises or a vacuum erection device (sometimes called a penis pump) may also be used.

You should know, however, that after reviewing the available data, the American Urological Association's guideline panel on erectile dysfunction recommended informing all patients that there is not convincing evidence that penile rehabilitation works for recovery of spontaneous, unassisted erections. Be sure to consider the costs and potential short-term side effects as you decide whether to take medications as part of penile rehabilitation.

Regardless of their use in rehabilitation, ED medications can help patients achieve erection for sexual activity after prostate cancer treatment. We also encourage patients to maintain intimacy with sexual partners during the recovery process; the emotional connection is as important as the physical recovery.

There are numerous protocols for penile rehabilitation. One UCSF protocol is detailed below. Please understand that this protocol hasn't been shown to be superior to any other, and there are no data suggesting it will reliably help with recovery. This protocol therefore should be taken as a suggested but not necessary part of ED recovery.

| Two weeks prior to prostatectomy |

|

| After catheter removal |

|

| Evaluation of sexual function 8 to 12 weeks after surgery |

|

| Evaluation of sexual function 12 months after surgery |

|

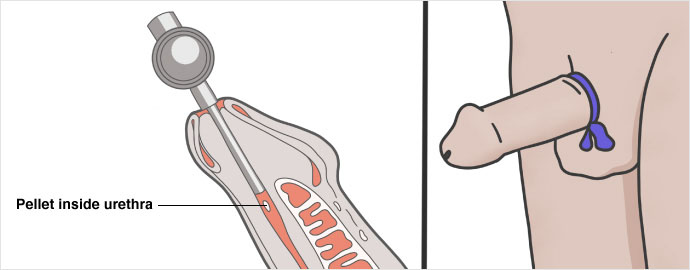

Urethral suppository (Muse)

To administer Muse, an acronym for medicated urethral system for erection, a small pellet of medication (prostaglandin E1) is placed inside the penile urethra. The medication is then absorbed and helps to produce an erection.

Muse may be used when oral pills are not an option or have failed. Large studies in both Europe and the United States have shown Muse to be effective – after dose adjustment – in 43% of patients with ED from various causes. The major advantage of this therapy is that it's applied locally and has few systemic side effects. However, Muse may cause significant penile pain and may be transferred to a partner during sex, leading to pain or discomfort for them. It should not be used by patients whose partners are pregnant because the main ingredient may induce uterine contractions. In rare cases, Muse may also lead to bleeding, dizziness or decreased blood pressure.

For patients who find Muse effective but painful, applying a small dose of lidocaine jelly to the urethra before placing the pellet may increase tolerance. Patients interested in trying Muse should receive instruction on proper technique in their provider's office; a test dose may be applied in this setting, so that side effects can be assessed.

| How to use Muse |

|

| Possible side effects |

|

| Things to remember |

|

Penile injections

When oral medication fails, penile injections to induce erection are another possible ED treatment. While the idea of injecting the penis may be unappealing, the needle typically used for these injections is thin and short; most patients are not bothered by it. The most commonly used drugs are prostaglandin E1 alone or a combination of drugs that increase blood flow, such as papaverine and phentolamine. Drug combinations, sometimes called bimix or trimix, may be more effective than single drugs alone and less likely to cause side effects.

Patients must have appropriate training and education before beginning penile injection therapy. The injections must be given in proper amounts with the appropriate technique in order to minimize the risk of penile scarring or priapism, a prolonged and painful erection that can cause permanent damage.

The medication is injected on one side of the penis into the corpora cavernosa, spongy tissue on either side of the shaft that contains the blood vessels involved in producing erections. Patients can administer the injection themselves, enlist a partner to help, or use an auto-injector (a spring-loaded device that inserts the needle quickly, minimizing psychological hesitancy).

Learn more about penile injection therapy.

| How to perform penile injections |

|

| Side effects |

|

| Things to remember |

|

Vacuum erection device

A vacuum erection device, or penis pump, may be helpful for patients who have only partial erections or who don't respond to or want to use other treatments. The device consists of a plastic cylinder connected to a pump and a constriction ring. Either manual or battery power is used to create suction around the penis and draw blood into it; the constriction ring is then released around the base of the penis to keep blood in the penis and maintain the erection. The device may be used safely for up to 30 minutes, at which point the constriction ring should be removed. The advantages of such a device are that it's relatively inexpensive and easy to use and there's no concerns about drug side effects or interactions. Possible side effects of the device include temporary penile numbness, bruising, and semen trapped by the ring. Some patients also report that the erection they obtain with the device feels somewhat artificial.

Penile prosthesis

For men with ED who don't tolerate or respond to other treatments, a penile prosthesis offers an effective yet more invasive alternative, requiring surgery. Prostheses come in either a semirigid form or as an inflatable device. Most men prefer the inflatable prosthesis because it permits a more natural appearance when the penis is flaccid.

Patients are under general anesthesia (completely asleep) for surgical placement of the prosthesis. An incision is made in the skin at the penis-scrotum junction. The spongy tissue of the penis is exposed and dilated; the prosthesis is sized; and then it's placed inside the erectile tissue.

The pump containing the inflation and deflation mechanism is placed in the scrotum. The patient can control his erection at will, using the hydraulic pump to inflate and a release button to deflate the prosthetic implant. Because the nerves that control penile sensation are not injured, penile sensation and the ability to have an orgasm are typically maintained after placement. Full penile length may not be restored to the patient's natural erect status.

Despite the need for surgery, patient and partner satisfaction rates for penile prostheses are as high as 85%. Side effects are rare but include infection, pain, and device malfunction or failure.

Future directions in treatment

Significant strides in scientific understanding of the anatomy and physiology of sexual function are aiding the development of new therapies. For instance, more detailed knowledge of the cavernous nerves in the pelvis led to the refinement of nerve-sparing prostatectomy. Understanding the biochemistry of normal sexual function led to the development of ED medications, including Viagra, Cialis, Stendra and Levitra.

Current research is focused on better understanding the specific physiological pathways responsible for normal sexual function, developing more effective agents for managing ED, and learning how cavernous nerves heal and what factors can hasten the healing process.

An intriguing line of inquiry over the past 10 years has been treating the penis with low-intensity shock wave therapy (LiSWT). This counterintuitive approach to treating ED with energy transfer is based on a growing body of evidence suggesting that shock waves may stimulate new blood vessel growth, reduce scarring, and activate resident stem cells to help restore tissues. The pulses used for ED therapy are similar to – but less intense than – the shock waves that have been used for decades to treat urologic stones.

A number of small, randomized, placebo-controlled studies have demonstrated benefits to erectile function in patients treated with shock waves to the penis. Unfortunately, the bulk of studies to date had limited follow-up, with most reporting out results at a mean of one month. Longer-term follow-up and data collection are topics of active inquiry, but currently there are no data to suggest that LiSWT will work as a single treatment for the majority of patients with severe ED related to prostate cancer treatment. LiSWT may eventually have a role as part of a multimodal protocol, but at this time it should be considered experimental.

Causes of ED

ED is most commonly related to aging, but it also has a wide range of psychological, neurological, vascular, hormonal and pharmaceutical causes, and may result from radiation and surgical treatments for prostate and bladder cancer. This table lays out the basics, and more detailed explanations for each cause follow.

| Category of ED | Conditions associated with ED |

| Psychological |

|

| Neurological |

|

| Vascular |

|

| Hormonal |

|

| Drug induced |

|

| Other conditions associated with ED |

|

Aging

Aging causes a progressive decline in sexual function even in healthy patients. Studies show that as men age, erections become less turgid (stiff) and the force and volume of ejaculation decrease. Also, with age, more time is needed to achieve another erection after orgasm (the so-called refractory period). Sensitivity to touch decreases over time, as do testosterone levels, and both changes can diminish sexual desire.

While it's not possible to reverse the effects of aging, there's no age at which a person is too old for sex. Men can avoid or at least delay the most severe manifestations of age-associated sexual dysfunction by remaining physically active, sticking to a healthy diet, avoiding weight gain, not using tobacco, and generally doing things that promote heart health.

Cancer treatments

ED is the most common side effect of both surgical and radiation treatments for prostate cancer.

The cavernous nerve bundles – the nerves that drive erection – are located next to the prostate gland. During a radical prostatectomy, these nerves may be injured. In many cases, this results in ED that is permanent, although the degree of dysfunction may be lessened through treatment. Because the prostate makes most of the fluid in semen, patients who have undergone prostatectomy don't experience ejaculation.

Radiation to the prostate, bladder or rectum also can damage the cavernous nerves and lead to problems with erections and ejaculation. These effects usually manifest a few years after treatment. Although ED and absence of ejaculation are common after prostate surgery or radiation, sexual desire and the ability to achieve orgasm are still possible. Doctors may be able to use nerve-sparing approaches in surgery or radiation therapy that can preserve one or both nerve bundles. While the nerve-sparing technique preserves the possibility of penile erections, most patients nevertheless experience a decline in erectile function that may never be completely recovered.

Hormone therapy for prostate cancer (androgen deprivation therapy) can also cause ED. The drop in testosterone reduces libido and can lead to erection difficulties. Whether these effects are reversible is related to the patient's age, degree of sexual function he had before treatment, and length of time on hormone therapy.

Psychological conditions

Depression and performance anxiety both can lead to ED. Depression is associated with decreases in energy, interest in usual activities and libido. Performance anxiety, work stress and strained personal relationships also can affect erectile function in both conscious and subconscious ways.

Neurological conditions

Penile erection depends on an intact nervous system, so any neurological injury or disease can cause ED. Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, stroke or head injury can lead to ED by affecting the libido or by interfering with the nerve impulses responsible for erections. Spinal cord injuries cause a decrease in erections related to the extent of the injury. Pelvic surgery – such as radical prostatectomy, cystectomy or colectomy – may injure the nerves that control erection. Long-standing diabetes may affect some nerves and lead to ED.

Hormonal changes

Anything that decreases circulating testosterone in the body, including undergoing chemical or surgical castration or hormone therapy for prostate cancer, decreases libido and may make natural erections more difficult.

Vascular damage

A variety of conditions and habits can damage penile blood vessels over time and contribute to ED. These include:

- High blood pressure

- High LDL ("bad") cholesterol or low HDL ("good") cholesterol

- Heart problems

- Cigarette smoking

- Diabetes mellitus

- Pelvic radiation therapy to treat prostate, bladder or rectal cancer

- Peyronie's disease (scarring with curvature of the penis)

- Traumatic injury

- Damage to the penile spongy tissue that results in leaky veins (sometimes associated with aging)

Chronic disease

ED is common in patients with diabetes, cirrhosis (liver scarring), chronic kidney failure and many other chronic medical issues.

Drug effects

Many types of drugs are associated with developing ED. Here are some to be aware of:

- Certain antidepressants (including Prozac, Zoloft and Paxil) and antipsychotics, especially those that regulate serotonin, noradrenaline or dopamine.

- Beta-blockers and thiazide agents used to treat high blood pressure.

- Cimetidine, a drug for acid reflux disease.

- Heavy alcohol use or chronic alcoholism.

- Estrogens and drugs with antiandrogenic action, such as ketoconazole and spironolactone, can lead to ED, decreased libido and breast enlargement.

- Many drugs of abuse, including tobacco, marijuana and narcotics. (See table below.)

| Class of drug | Drug |

| Antihypertensive |

|

| Antiandrogens |

|

| Cardiac drugs |

|

| Diuretics |

|

| H2 antagonists |

|

| Antidepressants |

|

| Other drugs |

|

Additional information and resources

Mechanisms of penile erection

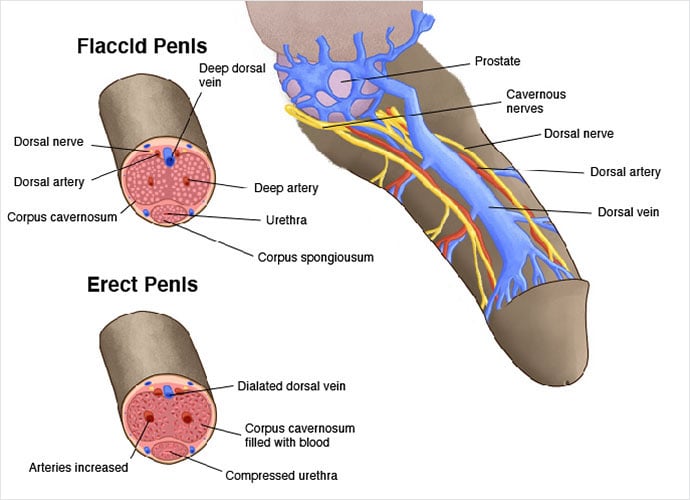

The cavernous nerves travel from the underside of the penis to the prostate. They regulate blood flow within the penis. In the flaccid state, relatively little blood flows in through the arteries and there is free outflow via the small veins exiting the spongy tissue just under the thick tunica (membrane surrounding the spongy tissue). During erection, the smooth muscle in the penis relaxes while the arteries widen to bring in more blood. This expands the three cylinders of erectile tissue in the penis, thus lengthening and enlarging the penis. The expansion of these cylinders compresses the small veins, reducing the outflow of blood.

The processes of penile erection are driven by the actions of nerves and blood vessels. Hormones, such as testosterone, also play important roles. Finally, a patient's psychological state and the health of his sexual relationship with a partner are critical determinants of sexual response. Stress, anxiety and depression activate the sympathetic nervous system; this is a natural response to any form of stress. However, that response tends to restrict blood flow into the penis and can make erections difficult or impossible. Careful attention to both mental and physical health is important in preserving erectile function.

A normal erection requires the penis to have intact nerves and blood vessel systems. Nerves that travel to the penis include fibers from the autonomic nervous system – the part of the nervous system that functions independently of conscious thought – as well as the somatic nervous system – the part responsible for sensation and contraction of muscles attached to the penis.

The autonomic nervous system controls the smooth muscle in the penis, prostate and urinary sphincter – muscle that is important for initiating erections and facilitating ejaculation. The autonomic nervous system has two parts. The sympathetic division tends to restrict penile blood flow and is important for closing the bladder neck to prevent urine leakage during sex. The parasympathetic division increases penile blood flow and stimulates erection. Coordination of these two components of the autonomic nervous system is critical to sexual response.

Sensory nerves travel to the head and shaft of the penis; these nerves are responsible for conveying sensations (such as touch, temperature and pain) to the brain and may be important for stimulating sexual response.

Motor nerves control contraction of the ischiocavernosus and bulbocavernosus muscles, which are necessary to producing a fully rigid erection and to ejecting semen during ejaculation.

With sexual stimulation, parasympathetic cavernous nerves release chemicals (primarily nitric oxide) that significantly increase blood flow to the penis. The erectile tissue of the penis rapidly fills with blood and expands, becoming firm and erect. With increasing sexual arousal, the somatic nervous system causes the bulbocavernosus and ischiocavernosus muscles of the penis to contract, forcing additional blood into the penis and making it very rigid. At peak sexual arousal, the sympathetic nervous system causes contraction of the prostate and seminal vesicles, leading to emission, which is the deposition of seminal fluid into the urethra. The sympathetic nervous system also makes the bladder sphincter close, preventing the semen from leaking into the bladder. As the amount of fluid builds in the urethra, pressure increases and the sensation of the inevitability of ejaculation is experienced. The bulbocavernosus muscle, which is under control of the somatic nervous system, then contracts and expels the semen forcibly from the urethra. Orgasm normally coincides with ejaculation.

Detumescence, or loss of erection, occurs shortly thereafter, as the nerves that trigger penile erection stop sending those signals.

Books

Saving Your Sex Life: A Guide for Men with Prostate Cancer, by John Mulhall, Hilton Publishing, 2010.

Going the Distance: Finding and Keeping Lifelong Love, by Lonnie Barbach and David L. Geisinger, Plume, 1993. Realistic book about maintaining intimacy.

Hold Me Tight: Seven Conversations for a Lifetime of Love, by Sue Johnson, Little Brown, Spark, 2008. Stellar book on communication and intimacy for couples.

Intimacy With Impotence: The Couple's Guide to Better Sex After Prostate Disease, by Ralph Alterowitz and Barbara Alterowitz, De Capo Lifelong Books, 2004. Written in an honest, compassionate style by a patient with prostate cancer and his wife. Discusses ED in nonmedical terms, with information on treatments. Gives practical advice about sex, covering everything from getting into the mood to common-sense suggestions for achieving sexual satisfaction and intimacy when erections are not possible.

The Lovin' Ain't Over: The Couple's Guide to Better Sex after Prostate Disease, by Ralph and Barbara Alterowitz, Health Education Literary Publisher, 1999.

Man Cancer Sex, by Anne Katz, Hygeia Media, 2010.

Men, Women and Prostate Cancer: A Medical and Psychological Guide for Women and the Men They Love, by Barbara Rubin Wainrib, Jack Maguire and Sandra Haber, New Harbinger Publications, 2000.

Websites

urology.ucsf.edu/patient-care/cancer/prostate-cancer

Erectile Dysfunction: AUA Guideline

Prostate Cancer Foundation: funds high-impact research aimed at finding better treatments and a cure.

Zero Cancer: a large nonprofit prostate cancer education and support network.

Men's Health Network: an educational nonprofit comprised of doctors, researchers, public health workers and other health professionals who focus on health awareness and disease prevention.

Other sources

American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy: 112 South Alfred St., Alexandria, VA 22314-3061; phone: (703) 838-9808, fax: (703) 838-9805

American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors and Therapists: P.O. Box 5488, Richmond, VA 23220-0488; phone: (804) 752-0026

American Cancer Society: phone: (800) 227-2345

CancerCare: phone: (800) 813-HOPE, (213) 712-8400

This article was written by UCSF medical expert Alan W. Shindel, MD, MAS, and UCSF patient advocate Stan Rosenfeld. It was last reviewed in May 2022.

This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended to replace the advice of your doctor or other health care provider. We encourage you to discuss any questions or concerns you may have with your provider.

Where to get care (1)

Awards & recognition

-

Among the top hospitals in the nation

-

Best in Northern California for urology

-

in NIH funding for urology research